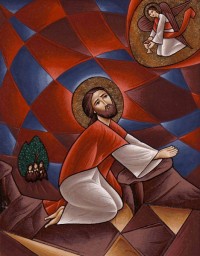

The Garden and our Prayer Life

A thought for Holy Week, based on an essay from a few years back.

When we look at the life of Jesus, can we see anything in his prayer life that can be used as a “pattern of spirituality” for our own spiritual journeys? Of course, to ask this question is to first determine whether such a “pattern of spirituality” can be discerned in the first place, and of what purpose that is. If the purpose is to simply catalogue Jesus’ prayer life then the question is not really a spiritual one but rather more a literary studies one. If however, the purpose of the question is to discern something within Jesus’ “pattern of spirituality” which can be copied, that Jesus’ devotional life has something to teach us, then the question becomes indeed one of  spirituality. However, approaching the question from this perspective raises the question whether Jesus’ prayers are indeed intended to be exemplary, and if so (or not) what that tells us about who he is and who we are.

When we look at the life of Jesus, can we see anything in his prayer life that can be used as a “pattern of spirituality” for our own spiritual journeys? Of course, to ask this question is to first determine whether such a “pattern of spirituality” can be discerned in the first place, and of what purpose that is. If the purpose is to simply catalogue Jesus’ prayer life then the question is not really a spiritual one but rather more a literary studies one. If however, the purpose of the question is to discern something within Jesus’ “pattern of spirituality” which can be copied, that Jesus’ devotional life has something to teach us, then the question becomes indeed one of  spirituality. However, approaching the question from this perspective raises the question whether Jesus’ prayers are indeed intended to be exemplary, and if so (or not) what that tells us about who he is and who we are.

I want to suggest that there are two types of prayers that Jesus prays. The first are prayers that are exemplar prayers, not so much that they are to be repeated (though some are) but rather that they exemplify the  type of prayer life that we  should have. The key thing about these prayers is that they stem from the humanity of Jesus, from his connection with each and every one of us.

The second type of prayer though is the non-exemplar prayers, those which we could never hope to copy. That is because these prayers stem from the divinity of Jesus, that they are the consequence of his divine being and as such belong in that realm and that realm alone. An attempt to use these prayers as exemplary would be to miss the point, that there are aspects of Jesus’ being (and function which stem from that) which are simply unrepeatable.

Exemplary Prayer

Jesus then is the example for our prayer life in that in his humanity he presents the perfect man in relationship with the creator. It was a relationship he zealously cultivated, making space and time to commune with his Father. I like how sister Margaret Magdalen puts it,

All night in prayer, frequently wandering off to the ‘certain places’ that the gospel writers speak of for long periods of solitude — what kind of prayer was this? What was the secret of the serenity, the inner strength and the authority which seemed to flow from Jesus when he returned from these prayer sessions? Did the disciples feel awed, slightly uncomfortable or even envious? Or did they perhaps feel all these things at once? There must have been something, a quality, an atmosphere — which they realised was different from anything they had met before, in themselves or in others.1

Margaret Magdalen suggests the simple solution to why Jesus’ prayer life was both dynamic and effective was that he has a personal relationship with his father and that that was the chief driver of his spirituality, not so much what he did but who he did it with and the awareness of the relationship with that “whoâ€. Jesus’ extension of the fatherhood of God to apply to all his disciples (Matthew 6:9) shows that the concept of God as Father was not restricted to just himself. This has led a number of commentators to focus on the relationship of Jesus with his father, trying to understand what this actually means for Christian devotion. This is certainly the observation of Joachim Jeremias, who devotes over half of his book “The Prayers of Jesus” to just examining “Abba”.

That referring to God as “Father’ was common practice in the Jewish communities of the time is not in question. Jeremias shows as much, demonstrating not just Scriptural references to God as Father but also Rabbinic2. God is not just a Father to the nation but also to individual Jews3.

Perhaps Jeremias’ most interesting research is in reference to God as Father by Jesus and where it occurs. What is striking is that while Matthew out-paces Mark and Luke in the word count, Matthew himself is outdone by John who presents over a hundred references by Jesus to God as Father. Jeremias would have us believe that this demonstrates a “growing tendency to introduce the title ‘Father’ for God into the sayings of Jesus”4, though a simpler understanding might be to merely observe that Matthew, as the most Jewish of the synoptics, is most comfortable using this increasingly normative Jewish form of reference to God. The fact that John uses twice as many references as Matthew is equally unsurprising for, firstly, he is reporting different events and, secondly, his Gospel is quite open in displaying a generation’s theological discernment of who Jesus is and his place in the Godhead. Given John’s advanced Christology, one would be more surprised if this observation did not occur.

Furthermore Jeremias’ insistence that the occurrence of “Father” in Matthew is redactive, particularly the usage of “Heavenly Father” seems to miss the point that simply the existence of material beyond Mark, or as a redaction of Mark by Matthew, does not necessitate a further redaction afterwards. That Matthew is more extensive than Mark means that by simple terms of a word count, “father” and variants thereof (“Heavenly Father” etc) are likely to occur in greater numbers than in Mark. Indeed, as I pointed out above, if Jeremias is correct that “Father” is a semitism5, then we would expect a greater occurrence in Matthew then in Mark.

This aside, Margaret Magdalen’s point is still valid, that it is the usage of “Father” in the personal, affectionate sense that marks the clear distinctive of Jesus’ prayer life. “Abba” as a form of address was / is the Jewish near-equivalent of “Daddy”, a form of affection that somehow seems inappropriate towards the creator and sustainer of the universe. As she puts it,

God was personal – of that the Jew was in no doubt. But he did not necessarily experience him as personal, i.e. have a personal relationship with him. In any case, his relationship would be as a member of the Jewish nation, not as an individual.6

lt is intimacy then which is the first example that Jesus gives us, intimacy which of course never denies the inequality of the relationship. God is God and we are not.

We can then develop upon the idea of intimacy, for intimacy requires manufactured space in which to grow. This is why Jesus takes himself off to a quiet space, not so much to “date the Father” but to find space and solitude to foster this intimacy, and yet not by definition solitude, for the Father is there. Sister Margaret Magdalen wonders whether this “quiet place” was not so much a physical environment but also a state of being

Each of us needs an oasis now and again, but if we live and work for most of the year amidst noise, and noise is our inescapable desert, we can still receive Christ’s gift of peace and carry it into that desert situation. Safeguarding the gift within, we can bring it into areas where it will disturb false peace … It was precisely because of these practical difficulties that Jesus told his disciples to cultivate a still centre inside themselves. “When you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret” (Matt 6:6) … Jesus must, therefore, have been speaking not only of a secret place as opposed to display in prayer but of that ‘portable inner sanctuary’ which we carry around with us and to which we can withdraw at any time and in any place … It is like a perpetual wayside shrine at which we can pause and worship throughout the day’s work.7

This reminds me of two things, firstly the “denkmal“8 littered all over Austria and southern Germany (my family comes from Austria) which provide places not so much for the wanderer to stop and reflect but more to have a spiritual input as they walk by. One also needs to remember that the Austrian/Bavarian culture is much more of a hiking and outdoors one then the British or North German. The idea of being out on a long walk is pretty normal, so the denkmal is something you would encounter in your everyday activity, not just on the off-chance you went for a wander into the mountains. This makes the Sister’s analogy more pertinent.

Secondly, it is the degree of intimacy implied that provokes (and which, for example, Â Theresa of Avila 500 years earlier captures so profoundly and provocatively) the notion that the deep longing for one who is different, the reminder of the other, of the relationship that one has with them, is the core of the prayer relationship. Jesus enters into a relationship of love with the Father and invites us too into that same relationship. The denkmal in the heart is not just a place of quietness that we pass at one time but in some greater sense a portable prayer place, a relationship not come to but rather carried along with oneself. Less gazed at as we walk past, more ported with us in our rucksack. The place of intimacy that Jesus presents to the disciples and us is then an invitation to literally fall in love with the Father and, having fallen in love, to long for the relationship to continue, to take it as a present reality through the world. As Michael W Smith sings,

And after all that we’ve been through

You’ve leaned on me, I’ve leaned on you

Do you dream of me?And when you’re smiling in your sleep

Beyond the promises we keep

Do you dream of me?9

It is the journey not just into intimacy but also the journey with the place of intimacy that is the character of Jesus’ prayer life. His activity on the cross then removes the barriers between humans and God which consequentially permits that prayer relationship to exist between each of us and the Father. This of course is why the disciples continually don’t get what Jesus is teaching, whether about prayer or otherwise, because the Spirit has not yet been released to regenerate them.

Non Exemplary Prayer

At this point I want to depart from Sister Margaret Magdalen’s understanding of Jesus’ prayer life as l want to suggest that there are some aspects of his prayer life which are non exemplary, in that they derive from his divinity and as such belong to his role as Christ. In particular, I want to concentrate on the great High Priestly prayer of John 17, for here we see Christ almost as it were “proclaiming himself” to the Father.

Jesus’ prayer to be glorified, having given glory to the Father, is a peculiarity that is not, I believe, intended as an example for believers. It is more than that, for it is a demonstration of his utter difference to those around him, his connection to the rest of the Godhead. Don Carson writes,

Although Jesus prays for himself in vv. 1-5, his praying is scarcely analogous to what we do when we pray for ourselves. There is but one petition: Glorify your Son … The associations here are complex. The verb “to glorify” can mean “to praise, to honour”, and something of that meaning is suggested by the fact that God’s purpose is that all should honour the Son even as they honour the Father (5:23). The very event by which the Son was being “lifted up” in horrible ignominy and shame was that for which he would be praised around the world by men and women whose sins he had borne. But in this context the primary meaning of “to glorify” is “to clothe in splendour”, as v. 5 makes clear. The petition asks the Father to reverse the self-emptying entailed in his incarnation and to restore him to the splendour that he shared with the Father before the world began.10

Carson believes (I think correctly) that the first part of the great High Priestly Prayer is a request from Jesus to the Father to return to heaven not as a “de-incarnation”. Rather, “when Jesus is glorified, he does not leave his body behind in a grave, but rises with a transformed, glorified body which returns to the Father and thus to the glory the Son had with the Father ‘before the world began'”11. This of course is the view of the writer of the letter to the Hebrews, who recognises both,

During the days of Jesus’ life on earth, he offered up prayers and petitions with loud cries and tears to the one who could save him from death, and he was heard … once made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him and was designated by God to be high priest in the order of Melchizedek.12

and

We do have such a high priest, who sat down at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in heaven, and who serves in the sanctuary, the true tabernacle set up by the Lord, not by man.13

Now, the point is this — the usage of the majority of Jesus’ prayers as being exemplary is contingent upon the non-exemplary prayer, which without its answer would render void any attempt to exercise as humans the exemplary prayers that Jesus prayed. It is only Jesus’ non exemplary prayer that initiates and submits to the action (the cross) that creates the union of saved man and God the Father, the union which allows humans to communicate with the Father. Where this takes us then is the extraordinary realisation that our prayer life is contingent upon the prayer life of Jesus, not just as an exemplar but in participating in his own unique act of devotion which, only then, frees the way for our acts of devotion.

This then is the supreme observation of the prayer life of Jesus, that his “Pattern of Spirituality” is not so much activities of prayer that can be observed and copied. Rather, the supreme prayer that he prays is unrepeatable, and that is the primary key for discerning anything from his prayer life at all. An attempt to concentrate on the human side of Jesus’ prayers (i.e. the exemplary prayers) completely misses the ultimate “spiritual act” upon which all his other acts, and ours, are contingent.

Jesus’ non-exemplary prayer is the trigger for our prayer life, for it initiates union with the Father which we ourselves could never manage. As such, one wonders whether it is devotional meditation upon this prayer which is far more useful than to simple copy Jesus’ exemplary prayers (not that that would be without merit), for the latter simply engages in the function of prayer, whereas the former enters the mystery of why that prayer occurs in the first place. It is the union which he accomplishes, of God and man, incarnated within his very self, which is the pattern to be observed above all things.

No one could describe

the Word of the Father;

but when He took flesh from you, O Theotokos,

He consented to be described, and restored the fallen image to its former beauty.

We confess and proclaim our salvation in word and image.

Kontakion of the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Notes

- Magdalen, Margaret; Jesus : Man of Prayer; p58

- Jeremias, Joachim; The Prayers of Jesus; pp11ff

- Jeremias, Joachim;Â The Prayers of Jesus; p21

- Jeremias, Joachim;Â The Prayers of Jesus; p30

- Jeremias, Joachim;Â The Prayers of Jesus; p33

- Magdalen, Margaret;Â Jesus : Man of Prayer; p61

- Magdalen, Margaret;Â Jesus : Man of Prayer; pp45-46

- German lit. “Think a moment”

- Grant, Amy; Darnall, Bev; Smith, Michael W; Do you dream of me; 1993 Age to Age Music

- Carson, Don; John; p554

- Carson, Don;Â John; p555

- Hebrews 5:7-10

- Hebrews 8:1-2

0 Comments on “The Garden and our Prayer Life”